The SIBAM Trauma-Healing Model

Sep 30, 2025

The SIBAM Trauma-Healing Model

Cornelia Elbrecht AThR, SATh, SEP, ANZACATA, IEATA, IACAET

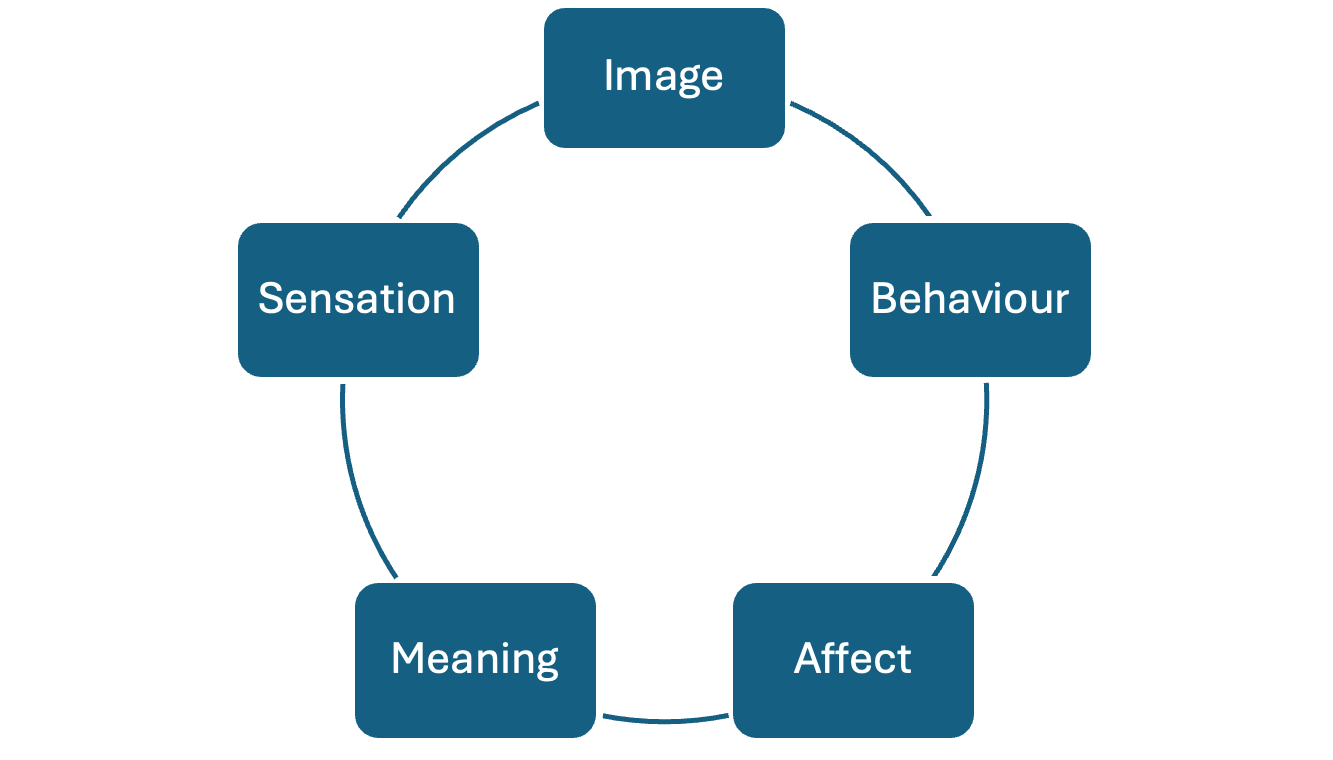

SIBAM stands for Sensation, Imagery, Behaviour, Affect, and Meaning, offering a structured pathway for engaging with trauma through the body and mind. The SIBAM model, developed by Peter Levine, the founder of Somatic Experiencing, enables us to understand and work with dissociation. Levine identified five main channels or component pieces that form a complete experience.

A complete experience could be the following: we feel relaxed in our body, because the sunshine warms our skin (Sensation), we take in many sensory cues such as hearing the ocean, smelling the sea air and seeing the waves rolling in (Image). Yes, we are walking hand in hand along the beach (Behaviour), my heart sings with happiness (Affect), because it is the best way to spend a Sunday afternoon with my family (Meaning).

However, when something overwhelming happens, such an experience splits into fragments. Rothschild (Rothschild 2000) and Levine (Levine, 2010) both state that we dissociate the most stressful elements of an event and only remember the bearable parts. In this context some parts of the experience might get over-emphasized, like a sound or a smell, and others become split off such as the bodily sensation during the event, or affect, because they were too unbearable.

Figure 1: The SIBAM Model by Peter Levine and Babette Rothschild

The five core elements in Levine’s SIBAM model are:

- Sensation, which marks the felt sense. This includes muscle tone (tension or collapse), your relative position in space (like how far or close to something you are), along with sensation from your organs (like your heart rate, breath and viscera). In therapy, these sensations, such as tension, warmth, or tingling, are viewed as pathways to uncover body memories, including trauma. By tracking, drawing, mapping and naming these bodily sensations like in Guided Drawing, clients begin to actively communicate with their physiological responses. (Elbrecht, 2018)

- Image includes all impressions we take in through the five senses: sound, taste, sight, smell and touch. Imagery involves the visual scenarios associated with memories, but it includes the other senses as well. Many survivors of bushfires, for example, have strong smell memories, others are triggered by certain sounds. These memories help bridge the gap between the body and the mind.

- Behaviour is the only one observable from the outside. This category includes gestures, facial expression, and posture. It refers to how clients physically respond during therapy, including body language, involuntary movements or the haptic connection of the hands in the Clay Field. (Elbrecht, 2021) Therapists can observe these behaviours to identify signs of stress or release, such as a shift in breathing, a spontaneous gesture or visceral changes like the sound of gurgling in the belly that points to the digestive organs coming out of metabolic shutdown (Porges 2011). These subtle cues can indicate progress as the body processes and integrates trauma.

- Affect is the emotion we felt at the time of an incident. In therapy they describe the way these feelings are expressed through tone, language, or facial expressions. Guided Drawing and Clay Field Therapy encourage the active expression and release of such affect through movement patterns. (Elbrecht, 2013, 2018, 2021) Line quality in drawings and haptic pressure when working with clay can vividly bring affect out into the open without the need for words. Observing changes in emotional expression helps therapists track how clients process affect connected to their trauma. Clients also learn to regulate these emotions, moving away from overwhelm toward balance.

- Meaning refers to understanding what happened. Meaning focuses on the client’s interpretation of their experiences. Through reflective conversations, clients make sense of the sensations, imagery, behaviours, and emotions they’ve explored in therapy. This step fosters cognitive integration and empowerment. The updating of long-held old belief systems may lead to post-traumatic growth, allowing clients to view their trauma in a new light.

During a traumatic event the most disturbing parts will be dissociated while other fragments of the experience can be remembered. This is a form of self-protection and a creative way our ANS helps us to survive. I find many clients stress a lot about not remembering fully what happened to them - especially whilst they were very young, when their boundaries were violated and they had no ability to fight or flee. The traumatic memory is blocked out to the extent that many question if they are making it all up; they wonder, if the abuse really happened, because they do not consciously remember it.

However, other symptoms might strongly indicate that something overwhelming did occur, which left these individuals with lifelong symptoms of dissociation, dysregulation, unpredictable stress-responses or trauma-related physical illnesses such as medically inexplicable pain symptoms, body weight issues, chronic disease, or else. (Van der Kolk 2014) PTSD of war veterans has been researched extensively in this context to explain their fragmented memories, which may erupt in nightmares or out of context, but can’t be accessed at other times.

During a panic attack, for example, Sensation and Affect are remembered, but all the other elements are dissociated, which makes it so hard to know what triggers the panic attack in the first place. The client experiences disturbing physiological reactions and fear, but without any known context.

|

|

Figure 2 & 3: Guided Drawing images showing different bilateral movement patterns for release.

I have worked with communities who have gone through natural disasters and found that Meaning is often the most affected component that needs to be restored. The question of: Why did this happen to my family and not to my neighbour? can be perceived as a divine curse and it becomes important to rebuild trust and faith.

Rothschild writes: “Once the missing elements can be identified, they can be carefully assisted back into the consciousness when the client is ready.” (Rothschild 2000) However, with children this does not work as easily, because many events happened to them before they had language, and the ability to critically observe the actions of adults. Their ANS may have never learnt to be organised in the first place. Children, for example, may exhibit repetitive play (Behaviour), but do not display any emotion (dissociated Affect) or appear to remember anything at all (Image). (Rothschild 2000)

Many children react with immobility in their body. (Levine and Kline, 2007) They repeatedly complain about tummy aches, headaches or asthma. They develop digestive problems or bedwetting. They display postural problems such as raised shoulders or being hunched over. They have trouble coordinating their hands and feet. Emotionally they feel shame and guilt or just do not seem to enjoy anything. Their behaviour is avoidant such as not wanting to go to certain places. They may become clingy and regress to younger behaviours. But they will rarely be able to tell any concerned adult what has happened to them.

|

|

Figure 4 & 5: Clay Field Therapy is a trauma-informed modality suitable for working with both child and adult clients.

One of the most important trauma-informed interventions for clients in shutdown is movement. How can they come back to life? Dissociative freeze states are characterised by immobility. Porges identifies the state as metabolic shut-down, which is characterized by I can’t, and often this manifests as: I can’t move, I can’t breathe or I can’t do this. It is rarely the case that the whole individual cannot move. Rather certain parts are dissociated, such as the frozen shoulder, or a child will only work with one hand in the Clay Field and the other arm hangs down at the side as if dead.

Sensorimotor Art Therapy with its body-focus is empowering for clients as the healing of traumatic events does not depend on a story and cognitive recollection. Instead, it allows them to express themselves in a range of ways that do not require language. Guided Drawing and Clay Field Therapy give clients agency to find active responses rather than feeling overwhelmed and helpless.

Levine’s research has always focused on a titrated active response as a way for clients to complete their thwarted survival response; how they can now engage with the defensive action patterns of flight or fight that occurred in the seconds before they froze in terror. Such active responses reset the trauma triggers in the brainstem and the ANS and shift clients out of dissociation. Clients can call back their dissociated parts, like a shaman they can retrieve the soul that once took flight.

Works Cited

Elbrecht, Cornelia. 2018. Healing trauma with guided drawing; a sensorimotor art therapy approach to bilateral body mapping. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

—. 2021. Healing traumatized children at the clay field; sensorimotor embodiment of developmental milestones. Berkley CA: North Atlantic Books.

—. 2013. Trauma healing at the clay field, a sensorimotor art therapy approach. London/Philadelphia: jessica Kingsley.

Levine, Peter. 2010. In an unspoken voice; how the body releases trauma and restores goodness. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

Levine, Peter, and Maggie Kline. 2007. Trauma through a child's eyes. Awakening the ordinary miracle of healing. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books.

Porges, Stephen, W. 2011. The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-regulation. New York: W. W. Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology.

Rothschild, Babette. 2000. The body remembers. New York: Norton and Company.

Van der Kolk, Bessel. 2014. The body keeps the score. New York: Viking, Penguin Group.