Mandala

Nov 28, 2025

Mandala

Cornelia Elbrecht AThR, SATh, SEP

Mandala in Sanskrit translates as circle. Mandalas appear in all world religions and have been used in a ritual context since the earliest of times. The circular designs reflect the underlying structure in all nature. Because of this deep connection to the bio-logos, the law of nature, they can restore order within a congregation of people or reconnect you to an inner order.

Mandalas appear in three major areas:

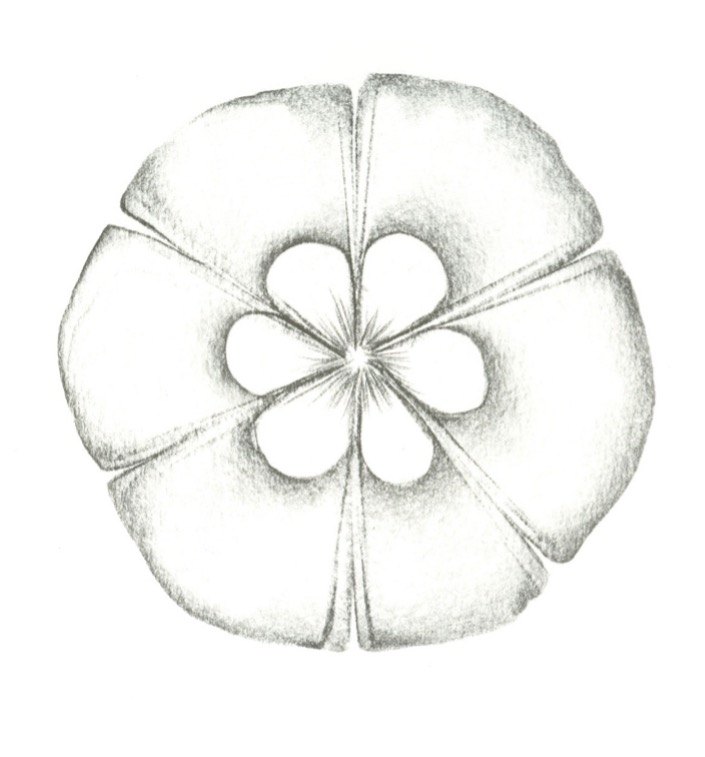

IN NATURE, they are the core structure in the micro- and macro-cosmos. Each cell, each atom, each snowflake, each flower, each fruit is a mandala. You can easily see this, when you slice through a carrot, an apple or the rings of a tree. The Milky Way is a mandala, as is the eye.

RITUAL MANDALAS mimic the order of nature as a transpersonal, collective reconnection with our inner nature. It appears as the Buddhist Wheel of Life, in Hindu Yantras, the Catholic monstrance and in many church windows. It is pictured as Celtic cross, Tibetan Thanka, Native American sand-mandala, as sacred dance, circumference of the Kaaba by Muslims, as prayer round of priests and circumambulation of shamans and witches. Ritual mandalas can appear as a fixed design, copied throughout the ages by dedicated monks, nuns and artists. They can be celebrated as circular dance, as ritual meeting around a sacred fire or the heated rocks in the sweat lodge. Ritual chants are also circular.

INDIVIDUAL MANDALAS appear intentionally or unintentionally in people’s drawings in a therapeutic or recreational context or as a form of meditation.

Mandalas appear in the process of Guided Drawing (Elbrecht, 2018) and in the Clay Field (Elbrecht, 2013) as a natural expression of oneness and healing. As a therapist I experience them as a most effective way of crisis intervention. I love mandalas and have drawn them since I was six years old. Most mandalas happen unintentionally: many clients don’t know they are drawing one, just as I was not aware that the circular designs I painted as a child were called mandalas.

|

|

A mandala consists of three main components:

The centre can be any marked point, circle or image in the centre of the page or any other marked space. In the famous Zen circles, the fertile void in the centre is left empty, marked as a dimension outside the known time-space continuum. It represents the Self as Carl Jung (C. G. Jung 1990) (C. G. Jung 2009) defines it, an intangible, invisible, inexplicable divine core.

The boundary is a frame or protecting shape on the outside, which is more effective with intentional corners rather than a circle, if such an emphasis is necessary. Such boundaries can have gates as in Tibetan mandalas. There can be several layers of boundaries, and they may have a specific significance, though not necessarily. The number of corners, as square, hexagram, octagon or more, is up to the individual and may or may not be charged with meaning.

The space between the centre and the boundary can represent “my garden”, “my room”, my sacred place. This space can be designed entirely according to one's likes. In most designs the structures relate to the centre and are balanced around it. Something at the bottom may ask for a corresponding shape or image at the top. A design on the left needs its counterpart on the right. These do not have to be symmetrical but can include opposites such as dark and light, happy and unhappy, heaven and earth.

In the MARI Mandala Assessment scheme Joan Kellog (Kellogg 1984) distinguishes between mandalas with a:

- diffuse and emerging centre such as an unfolding spiral

- ego-structured mandalas like those grouped around a cross or contained in a squared circle

- ritual mandalas that emanate light from their centre

- fragmented mandalas with a disintegrating core that represent death and falling apart

- rebirthing and resurrection mandalas, which she calls transcendental ecstasy where the fragmented parts find a new order.

You can draw mandalas with both hands rhythmically, as in Guided Drawing, or with open eyes and one hand. It is not necessary to construct a perfect round with ruler and compass. A mandala does not have to be beautiful. It can be and should be a space where you can bring your problems. In such a case, I would ask you for example to picture your problem as a large lump. Since this lump all in one spot will bring imbalance to your mandala, however, the mass can be subdivided into many small lumps. These can then be placed or carried around the centre. This circumambulatio, as the Alchemists called the process of a ritual circumference, is a healing ritual where all is surrendered to the centre. The centre as Self or spiritual core has the capacity to transform whatever matter is placed around it.

|

|

There are many ways to work with mandalas and many ways to introduce it to a client. I have facilitated mandala workshops for school-age children in combination with guided meditations, for groups of professionals to improve their communication skills, as couple therapy and, of course, as a form of joyful prayer. I have supervised mandala-drawing processes with children suffering attention deficit disorder, as life review with the elderly in nursing homes and in hospitals with the mentally ill. Joan Kellogg simply handed round picnic plates to her psychiatric patients to provide the sacred circle.

I have found mandala-drawing to be one of the most healing and empowering structures for clients in crisis. Mandalas provide a profoundly safe tool for therapists and are a key focus of our Certificate in Initiatic Art Therapy training. It is deeply stabilising and reconnects individuals with an organic order. Clients can draw mandalas at home, which can be comforting, have a self-protecting function and can banish intrusive thought patterns. Some keep mandala diaries. Such mandalas can be (but do not need to be) artistic. A mandala provides and evokes focus, structure and boundaries, elements a client in crisis usually lacks.

The Self as such has no name and no form. As our divine core it is intangible. The only way to connect with the Self is through circling around it. The Self is nothing we can have, own, control or manipulate. We can only focus on it, set our sights on it to be closer to the divine. This is the purpose of mandalas, be it as drawing, dance or prayer round. Drawing a mandala teaches us the unfolding of the inner process. By “listening” to our centre, we receive inner guidance.

Religious groups and individuals alike have used mandalas as a visual prayer to put their souls into order, to realign themselves with the divine in crisis and in joy as a regular meditation practice, to sing the song of our souls. Drawing or creating them is a reminder that every atom on this planet is a breathing, pulsing mandala, continuously creating and transforming matter as spirit flows through it. It is a way to surrender our controlling egos to the awe-inspiring eternal.

Works Cited

Elbrecht, Cornelia. 2018. Healing trauma with guided drawing; a sensorimotor art therapy approach to bilateral body mapping. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

—. 2013. Trauma healing at the clay field, a sensorimotor art therapy approach. London/Philadelphia: jessica Kingsley.

Jung, Carl Gustav. 2009. The red book; liber novus. New York, London: W. W. Norton & Co.

Jung, Carl, G. 1990. Man and his symbols. London: Arcana.

Kellogg, Joan. 1984. Mandala: path of beauty. Washington: Salish Sea Books.